Essay by Andrea Vitali, 2019

The art publisher Lo Scarabeo (Turin, Italy) published this year (2019) the Visconti di Modrone Tarot deck with a book written by Andrea Vitali on the history, iconography and iconology of the Triumphs (1). Purpose of the work, an exclusive for the American market, is to present the entire deck through a reconstruction of the Triumphs and other missing cards, based on the period of realization (indicatively the second half of the XV century) and on the iconography of the other Visconti decks. The english translation is curated by prof. Michael S. Howard, author of the essay Allegory and Game included in the volume.

The following is what Andrea Vitali wrote on the history of the surviving Triumphs, as well as their iconography and iconology. For a broader examination of the above-mentioned Triumphs, read the Iconological Essays, except for the three theological virtues.

Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, February 2019

The Visconti di Modrone Tarot deck (also called the Visconti and Cary-Yale), is one of three surviving hand-painted tarots with Visconti heraldic features, together with the Brera-Brambilla and the Colleoni-Baglioni (also called the Visconti-Sforza and Pierpont-Morgan-Bergamo). The Visconti di Modrone family sold these cards to Melbert B. Cary Jr., whose widow, Mary Flagler Cary, subsequently offered them as a bequest, along with the rest of his collection, to the Yale University Library, where they remain today.

The cards, measuring 189 mm x 90 mm, are slightly larger than those of the other two decks, and are made from overlapping sheets of card stock probably pressed in a mold, with a background decorated, using a puncheon, with diamond shaped motifs bearing the radiant sun, emblem of the Visconti family. The suit cards are characterized by a silver background with floral motifs. The deck is incomplete in the number of Triumphs (i.e. trumps or major arcana), while, unlike other decks, there are six court cards: the two additional cards represent female counterparts to the male page and male knight, thus supporting the neo-feudal taste of the 15th century courts.

As with all 15th century illuminated or hand-painted decks, the production of these cards involved numerous costly materials. This included a hot press for the card stock, pure gold and silver leaf, sharp puncheons and a series of burins with points at various angles (including almond-shaped, half-round, flat with a square section, flat with stripes), the finest chalk and blue lapis lazuli pigments, a good dose of carmine as well as purple and ruby red for the clothes, along with a brilliant yellow for the highlights, then ight and dark greens for the grass, as well as the colors indigo and violet; finally, brushes and of course pressed and curved card stock, each almost twenty centimeters long and nine centimeters wide, as was the average size of cards made for the courts at that time.

The dating of its creation is controversial: Giuliana Algeri placed the deck in the period of the marriage of Galeazzo Maria Sforza with Bona of Savoy (1468), a date that would make it the most recent of the three Visconti decks, as the work of two different artists, the first making the numeral cards at the time of Filippo Maria Visconti, while to the second, Bonifacio Bembo, would be attributed the Triumph cards. For Mulazzani, on the other hand, it was the oldest deck, the work of Michelino da Besozzo. Finally, Sandrina Bandera, noting, among other things, the presence of the same coin that is found in the Brambilla deck, dated to the time of Filippo, that is, “by 1447,” the year of his death, again by the hand of Bembo.

The deck, now incomplete, is composed of eleven Triumphs, seventeen court cards and thirty-nine numeral cards. Among the eleven Triumphs we find the three theological virtues in addition to the cardinal virtue Fortitude (Strength), whose presence leads us to assume that Justice and Temperance were also part of the original deck. The surviving Triumphs are, in addition to those mentioned above, the Empress, the Emperor, Love, the Chariot, Death, Judgment and the World.

Absent among the standard Triumphs are the Magician, the Popess, the Pope, Justice, the Hermit, the Wheel of Fortune, the Hanged Man, Temperance, the Devil, the Tower, the Star, the Moon, the Sun, and the Fool: fourteen in all. Missing among the court cards are the male page and male knight of Swords, the king and male knight of Staves, the male page of Coins, and the female knight and king of Cups. The only missing card among the numerals is the three of Coins.

There is some evidence of a tendency in older decks to balance the number of Triumphs with that of each suit, that is, of 14 Triumphs in a deck with 14 cards per suit. As this deck is composed of suits of 16 cards between numeral and court, we can hypothesize that the Triumphs numbered the same, for a total of 80 cards. If this was the case, only five Triumphs would be missing from the original deck.

Stuart R. Kaplan suggested that the above cards of Faith, Hope and Charity may have substituted for the missing Pope, Star and Popess, respectively. Even granting this analysis, Hope would be equivalent to the Hanged Man, given the presence of the traitor Judas on that card [Hope], because of the inscription Juda traditor that characterizes him there (on this point, see the iconology of these Triumphs). Furthermore, Faith would be equivalent to the Popess card, which we know today conveys the same meaning, and the Pope would be associated with Charity as an agent in this capacity.

On the hypothesis that the artist has created a deck with 22 triumphs, replacing three of the standard cards as proposed by Kaplan, the deck would be composed of 86 cards.

However, it should be taken into consideration that the minchiate, even if it came later, had a large number of Triumph cards, as many as 40, as along with the standard cards there were the twelve zodiac signs and the four elements as well as the three theological virtues, while the suit cards were composed of the usual 14 cards, for a total of 97 cards. This implies a game with a different set of rules than those of the tarot at that time. And what if the Modrone deck were also conceived differently? The series could then have had the 22 traditional Triumphs, plus the three theological virtues, for an overall total of 25 Triumphs, which, together with the suits would have brought the total number of cards in the deck to 89. The art historian Giuliana Algeri in fact speculated that the artist who created the deck was inspired by the Minchiate. But if that was the case, a great many Triumphs would be missing, which seems rather unlikely. From another perspective,Michael Dummett pointed out that with 21 trick-taking triumphs plus the Fool (which had no trick-taking, i.e. “triumphal,” power), the ratio of such triumphs to cards per suit would be 21:14, i.e. 3:2. To keep the same ratio of triumphs to suit cards with 16 cards per suit, 24 triumphs plus the Fool would be needed.

Assuming the deck consisted of 22 Triumphs and an additional three, it would not have been considered a daring invention at the time, but simply a way to do something different from what was customary in that period, an activity that would have implied different rules of play, but in perfect harmony with tradition at the time. Consider also that a greater number of Triumphs could, from a symbolic point of view, express the superiority of a family line.

The Numeral and Court Cards

As far as the suit cards are concerned, they have many similarities to the ColleoniBaglioni deck, even if in our deck the background of all the cards is darker due to their being made with silver, embellished by floral patterns, without the mottoes a bon droyt on the Swords, Staves and Coins, and amor meo on the two of Cups. The first motto appears in the blue mantle of the female page of Swords as well as that of Coins, together, in the latter, with the Dove and Radiant Sun, emblems that characterize all the court cards of the suit of Coins. In particular, we note certain differences in the ace of Cups, which in the Colleoni deck is a fountain, while in ours appears as a heavily engraved chalice, in harmony with the rest of the cards in that suit. The Swords appear more refined in the handle from an artistic point of view, with the resumption of the blue color that characterizes the swords themselves with the exception of the tip which retains its golden aspect, while the Staves appear as actual long arrows, with quills in the lower gilt part and a tripartite tip at their ends. Moreover, while in the Colleoni tarot all the Coins bear the Radiant Sun, ours presents the front and back of the florin minted by Filippo Maria Visconti, as well as the Visconti Viper, or Biscione, on the two of Cups. This Viper, heraldic symbol of the Visconti, is portrayed in the act of swallowing or protecting, depending on the interpretation, a child or naked man. Among all the court figures, who appear richly dressed on a gilded background, the only peculiarity is represented by the king of Cups, depicted as an elderly man with a beard: an iconography that contrasts with the youthful kings of Swords and Coins in the Brambilla deck as well as the four young kings of the Colleoni-Baglioni deck.

Iconography and Iconology of the survived Triumphs

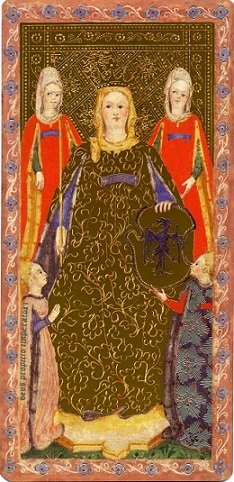

The Empress

The surviving Empress card portrays a crowned woman dressed in gold and ermine with a jousting shield in one hand and the baton of command in the other, accompanied by four damsels of much smaller proportions, as faithful followers were depicted at the time. On the mantle of the damsel on the bottom right, now faded, appears the inscription Deus propicio Imperatori (God is benevolent toward the Emperor). The eagle, imprinted in black, comes from the Visconti family in 1395 following the coronation as Duke of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, after which he obtained from the Emperor Wenceslas the escutcheon with the imperial eagle. The presence of the Empress in the order of the Tarot next to that of the Emperor is justified by Ecclesiastes 4: 9-11: “Two are better than one; because they have a good reward for their labor. For if either of them falls, the one will lift up his companion. But woe to the one who falls when there is not another to lift him up. Furthermore, if two lie down together they keep warm, but how can one be warm alone?” Since the Emperor reigned by divine will with the task of looking after his subjects, from a material point of view, he would have to be the first to set a good example, flanking himself with a wife.

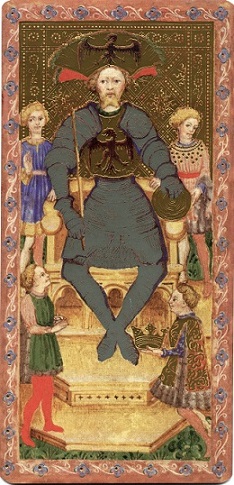

The Emperor

This original depiction shows a man seated on a throne, entirely covered in iron armor, except for his head which is adorned with a large fanned, feathered hat on which the Imperial Eagle is painted in black, repeated in gold on his chest armor. He holds the scepter in his right hand, while his left is resting on a golden globe, both symbols of command. He is surrounded by four pages dressed in various ways. The one kneeling at the foot of the throne holds a gold crown in his hands, while the tunic of the page at the lower section of the card to the Emperor’s right bears the motto “a bon droyt”: with good right [...we Visconti govern].

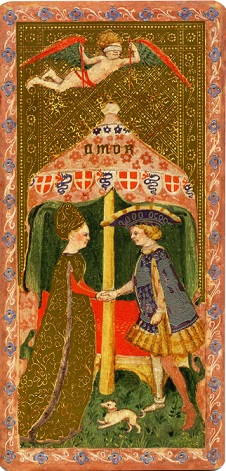

Love

This original card portrays matrimonial union through the ceremony of the dextrarum iunctio, that is, the joining of the right hands as a rite of indissoluble bond. It was a rite, resumed in the Middle Ages, which largely characterized the nuptial ceremonies of the Roman upper class, in particular the senatorial class. Above, endowed with wings, is Love as a child [Cupid], with eyes blindfolded according to the saying “Love is blind”; he drops two fiery arrows on top of the bride and groom, depicted in front of a canopy whose drapery, raised in the front, allows one to view the nuptial bed. The newlyweds have been identified by eminent art historians as Duke Filippo Maria, his head decorated with a large fan-shaped hat on which appears the usual motto a bon droyt, and the bride as Maria of Savoy. For Giuliana Algeri, the scene refers instead to the second marriage of Galleazo Maria Sforza when he married Bona of Savoy. The dog between the two was considered in the Middle Ages a symbol of modesty and loyalty. In the upper part of the pavilion in gold characters is the word Amor or Amore, while the border is entirely formed of blazoned shields, in which the Visconti Viper alternates with the white cross on a red background of Savoy.

The Chariot

The Chariot, which assumes in the tarot the value attributed by Petrarch to Fame in his famous series of poems Il Trionfi (The Triumphs), is defined by the monastic author of the Sermones as a mundus parvus, that is to say, ephemeral success, a small triumph, in relation to the fact that Fame, who gives to time the deeds of great men, will have to succumb to Time itself and above all to the only true unchangeable reality, that is, the Divinity that Petrarch expressed in the Triumph of Eternity. According to the concept of scholasticism, it was the recourse to reason that made the truths of faith comprehensible, suggesting a Christian and correct behavior for men and women, an attitude to be attributed to the woman guiding the chariot, covered by a kind of small gothic temple. It is perhaps the same Maria of Savoy, as she wears the same robe that appears on the previous card. In her hands she bears a scepter and a shield depicting the radiant dove of Visconti heraldry. The chariot is pulled by two white horses driven by a groom. The peculiarity of this card lies in the position of the chariot, usually depicted frontally, here instead in almost perfect profile.

Strenght

After Justice, the cardinal virtue, is Strength, called Forititudo in the teachings of the Church. In the original card it is represented by a woman wearing a large gold crown on her head. Her wide robe is made of silver brocade lined with ermine. Her seated position on the lion’s back, thus dominant and in the act of blocking the animal’s jaws, has its iconographic roots in the biblical narration of Samson and the lion of Timnah (Judges, 14:5). The moral meaning of Christian fortitude is exalted by the girl, who becomes a symbol of intelligence and reason dominating the lion, i.e. the earthly instincts and passions, meaning in addition the victory, through a serene strength, over the evil forces that put obstacles in the path towards salvation, an interpretation that seems quite evident because [in the literal sense] nobody, especially a girl, would dare face a lion with their bare hands. Fortitude is put in third place by St. Thomas, after Prudence and Justice and before Temperance; it is exercised when someone facing events that are tolerated with great difficulty, such as terrible evils, remains steady and constant in receiving them, or repulses them when it is necessary to remove them (2).

Death

Here Death, on a dark horse with his head wrapped with a fluttering white bandage, is depicted galloping and trampling on people lying on the ground, among whom is a pontiff and a cardinal, whose heads he severs indiscriminately with the large iron tool he holds in his hands. The Latin expression Aequo pulsat pede, from Horace (3), which can be translated as “[death] strikes with an impartial foot”, means that death makes no distinction between monarchs and subjects, rich and poor, young and old. If until the beginning of the 14th century death was conceived as a casual event that allowed entry into true life, from that time onwards, it participates, through the practices of the Ars Moriendi [Art of Dying], consisting of the exercises of the “Good Death” in a meditation on the physical destiny of man. Thus was born, through the disgust and fear of thinking of one’s own body in putrefaction, the sense of the macabre, a sense that the image of Death as depicted in this deck makes explicit: not entirely skeletal, with entrails tangled and skin covering the upper trunk of the body.

Judgment

Of the Last or Universal Judgment, the Holy Scripture speaks of Jesus foretelling to his disciples that one day he would return to judge the living and the dead, and then “When the Son of man […] shall sit on the throne of his glory […] and say unto them on his right hand: Come, ye blessed of my Father; inherit you the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world […]. Then shall he say also to those on his left hand. Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels.” (Matthew 25:31,34, 41) The upper part of this card, one of the originals, shows two angels with trumpets while in the lower part the dead arise from their graves. The writing surgite ad iudicium (rise to judgment) set above the angels’ wings indicates what is about to happen. A turreted building with a bell tower expresses the power-strength of the Mystical Church to which man must turn so as not to fall into sin, since the Judgment Day will happen to everyone and the divine power will evaluate each person’s actions. The pictorial representation of the structure, with the upper part of the bell tower put in the top part of the card, in the sky, and the fortress part firmly rooted on the earth, denotes the function of the Church as mediator or bridge between God and humans. Centrally, in the lower part of the card, a man half-length entering into the earth or going out from it, represents the article of faith regarding the concept of "Christ Descending to Limbo," a recurrent image in a particular style of iconographic depiction. In fact, the figure can be identified both with Christ in the act of going down to Limbo and with one of the figures rising up from Limbo, as a feature combined with that of Judgment, showing as one alternative Christ with the risen dead as mediator between them and heaven.

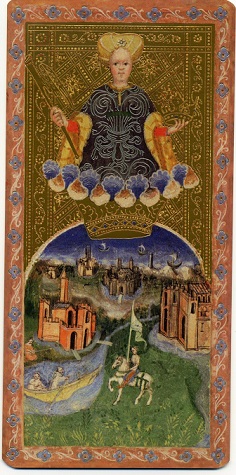

The World

A matronly woman shown half-length, richly dressed, with a trumpet in her right hand and a golden crown in her left, overlooks a large arch indicating the vault of the sky; on top of which we see a large golden diadem. Above this, a half garland of open shells, the upper ones blue to represent the sky, the lower ones brown to symbolize the earth, separate the matron from the scene below. If she herself is clearly identified as Fame by the trumpet, with which she can spread the news in the world below, and her power by the crown, the large diadem bears witness to her sovereignty over the world. Below the arch is landscape with ships sailing in the sea, a river within which appears a boat of monks rowing, while on the shores one can see on one side a knight holding a flag, likely representing the recipient of Fame or the one who seeks it, and on the other side a fisherman. The rest is mountains, towers, castles with moats, houses, fields, etc.

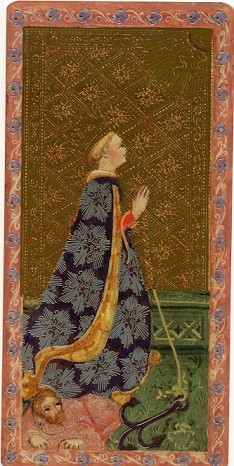

Hope

This theological virtue is represented in the usual way it was described in religious art at the time: a crowned woman, with her hands joined in prayer and her gaze turned toward a ray of light, from which she awaits salvation. From her right arm hangs a rope attached to an anchor – which recalls the cross, hope of every believer – lying on the ground, to represent the words of the Holy Scripture: “Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast.” (Hebrews 6:19) At the foot of Hope we see an old man lying on the ground with a noose around his neck, and the words, now faded but once visible according to testimonies of yore, Juda Traditor written in white characters. In this regard, this image follows the medieval tradition in which Judas represents the opposite symbol of Hope, (4) because he is considered the one who, lacking this virtue, took his own life without hope that Jesus would forgive him.

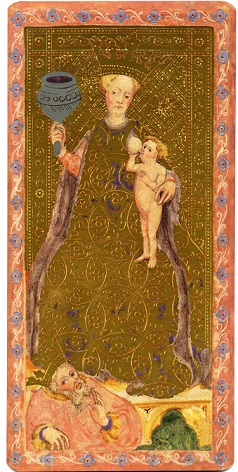

Charity

A seated woman, crowned and richly clothed in gold brocade with an ermine mantle, holds in her right hand a vase in which a flame burns, and with her left she supports a naked child nursing from her left breast. At her feet an old king, lying on the ground, appears in thought. The image does not differ from the typical depictions of this virtue, generally represented by a woman breast-feeding a child and holding a flame, symbol of ardent and impartial love for others. Its characteristic color is red. Charity is the theological virtue by which we love God above all else for His own sake, and our neighbors as ourselves, by the love of God. That is why Jesus said, “This is my commandment. That you love one another, as I have loved you” (John 15:12). Charity is the highest of virtues, the first of the theological virtues: “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity” (1 Cor. 13:13). If the charitable aspect is highlighted in the card by the breast-feeding of the child, the figure of the king below, thus dominated by the virtue, expresses a warning to every powerful person on earth to observe this teaching, because otherwise, they will find themselves, as the image expresses, crawling on the ground.

Faith

Faith is the theological virtue by which we believe in God and in all that he has said and revealed, and that the Church proposes to us to believe, because He is the same truth. By faith, “man freely commits his whole self to God” (5). For this reason, the believer seeks to know and do the will of God. “The just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17). Faith “works through charity” (Galatians 5:6). The gift of faith remains in one who has not sinned against it. (6). “But faith without works is dead” (James 2:26). If it is not accompanied by hope and love, faith does not fully unite the believer to Christ and does not make him a living member of his Body. This card, one of the originals, presents Faith as a woman who carries in one hand the attribute of the chalice with the wafer visible and in the other the cross, to signify not only faith, in virtue of the sacrifice of Jesus who died on the cross, but also (as the chalice shows) faith in the perpetuity of this sacrifice miraculously renewed every day on the altar, of which, the sacrament of the Eucharist is the most perfect symbol.

Notes

1 - From p. 7 to p. 58. The professor Michael S. Howard dealt with the playful-allegorical aspects (p. 68 -73), while Ms. Lunae Weatherstone of the divinatory part (p. 77-127).

2 - Gio: Battista Scaramelli, Vita della Ven. Serva di Dio Suor Maria Crocifissa Satellico, Capo XXII (Life of the Ven. Servant of God Sister Maria Crocifissa Satellico, Ch. XXII), In Venice, by Giuseppe Rosa, MDCCLXI [1761], p.259.

3 - Horace, Odes, I, 4, 13.

4 - Leone Dorez, La canzone delle virtù e delle scienze di Bartolomeo di Bartoli da Bologna (The song of the virtues and sciences by Bartolomeo di Bartoli of Bologna), Bergamo, 1904, p. 82.

5 - Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum, 5: (1965).

6 - Council of Trent, Session 6, Decretum de iustificatione (On Justification, First Decree), chapter 15.

Copyright by Andrea Vitali © All rights reserved. October 2019