Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, December 2014, with an Addendum to the same at the end of the Andrea Vitali's essay

'The sacrilegious Schismatics and impious Heretics, despite being punished, dare to peddle the punishment of their

pain, for true martyrdom' (Saint Augustine, Contra Parmen, Lib. 3, Section 6)

'God will separate them (on the Day of Judgment) as the shepherd separates the sheep from the goats' (Matthew, 25. Verse 32)

John Foxe (1516/1517 - 1587), often called ‘Fox’ by his detractors, was an English historian and martyrologist, whose history of the English Church was revered for centuries by Anglicans and relentlessly attacked by Roman Catholics for centuries, until in our day both sides are themselves the objects of historical scrutiny.

A Lecturer in Logic, until he became a Protestant and resigned, he wrote several works in Latin, including the De Christo triumphante or Christus triumphans, published in England in 1551 and translated into French in 1562.

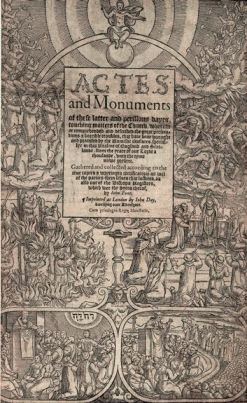

But his most famous work, published for the first time in 1563, has the title Actes and monuments of matters most speciall and memorable, happening in the church, with an universall historie of the same: wherein is set forth at large the whole race and course of the church, from the primitive age to these latter times of ours, with the bloody times, horrible troubles, and great persecutions against the true martyrs of Christ, sought and wrought as well by heathen emperours, as now lately practised by Romish prelates, especially in this realm of England and Scotland: now againe, as it was recognised, perused, and recommended to the studious reader (1), a work in which the author, besides recounting the history of the Catholic Church in England and Scotland before Protestantism, highlights the suffering endured by Protestants because of that same Church.

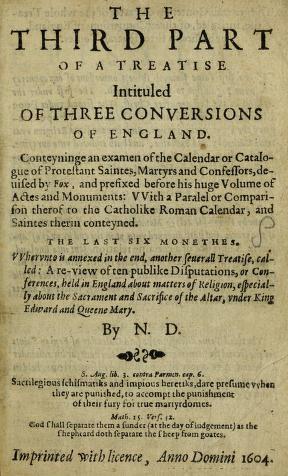

A bitter satire against Foxe was expressed by the Jesuit Robert Persons, or Parsons (1546-1610), in two installments, Parts One and Two in 1603 and Part Three in 1604. Part Three had the title Third Part of a Treatise intituled Of Three Conversions of England, Conteyninge an examen of the Calendar or Catalogue of Protestant Saintes, Martyrs and Confessors, devised by Fox, and prefixed before his huge Volume of Actes and Monuments: With a parallel or comparison thereof to the Catholike Roman Calendar, and Saintes therin conteyned. The last six monethes. VVhervnto is annexed in the end, another seuerall Treatise, called: A re-view of ten publike Disputations, or Conferences, held in England about matters of Religion, especially about the Sacrament and sacrifice of the Altar, vnder King Edward and Queene Mary (2).

The passage of our interest concerns a personage that Persons says Foxe considered a saint and martyr. In mocking this personage for what Persons considered extravagant, almost comical actions, he intended to ridicule Foxe as well.

About our man, whose name was Hugh Latimer (Persons, and Foxe sometimes, spell it 'Latymer', but English usage since has 'Latimer'), Foxe tells the story, entitling it The life, acts and doings of Maister Hugh Latymer, the famous preacher and worthy Martyr of Christ and his ghospell (3). The son of a farmer, Persons paraphrases Foxe, at fourteen Latimer was sent to Cambridge, where he became a “zealous papist and a servile observer of the Roman decrees", believing that if he became a monk, his soul would not be damned. His conversion to Protestantism came in hearing the confession of a certain Thomas Bilney (who later will die Catholic, Persons says). We do not know what the words were with which he was so impressed as to have a sudden change of faith, but the fact is that from that moment on, he began to be, Persons writes, "affected and infected by noveltyes” (novelties), covertly so as not to be discovered, while deriding the ceremonies of the Catholic church and criticizing the life of the clergy, an undertaking in which he had a particular talent,, as Persons writes "being (so to speak) a born buffoon" [being in deed borne (at yt were) to be a buffone or publike Iester] (4).

But one day, seized by zealous fervor, he "put his cards on the table": on the Sunday before Christmas in 1529, he ascended the pulpit of the Church of Saint Edwards at Cambridge to preach a sermon, but instead of dealing with the sacred mysteries, spoke on how to play Triumphs! This is the game of Triumphs we explained in the essay Triumphs, Trionfini, Trionfetti, played with so-called French suits, that is, with the suits of Spades (♠), Hearts (♥), Diamonds (♦) and Clubs (♣), used in England in the 16th century.

About Latimer, Persons then relates: “...Anno Domini, 1529: he made a sermon on playing at Cards, and taught them how to play at Triumph, how to deale the Cards and what every sort ther of did signifie, & that the Hart was the Triumph, addinge moreover (saith Fox) such prayses of that Cards (the Hart when yt was Triumph) that though yt were never so small, yet would yt take up the best Cotecard besides in the bunch, yea though yt were the Kinge of the Clubbes himselfe, &c. Which handlinge of this matter was so apt for the time, and so pleasantly applyed by him, that yt not only declared a singular towardnes of witt, but also wrought in the hearers much fruyt, to the overthrow of Popish superstition, and settinge up of perfect religion.

“Thus wryteth Fox of the beginning of Latymers preaching in Cambridge, and of his playinge at cards in the pulpit; a fitt exordium for such a ghospell, as after he vvas to preach, which commonly was euery vvhere begon with playes, comedyes, apes, poppets, iesting, sayling, rayling of sedition, or other like practises (which heere Fox calleth settinge up of perfect Religion) and not as Christs ghospell began vvith Agite poenitentiam, doe pennance, &c. And jow must know that this Cardinge sermon of Latymer in Cambridge, was one of the most spitefull, and seditious, that euer vvas heard before in England. For that vnder pretence of commendinge the Hart vvhich vvas Ttriumph in the Cards, & represented (forsooth) his new Religion, he inueighed most bitterly against most points of Catholike Religion, as though they came not from the Hart: and consequently also compared the teachers therof to Scribes and Pharisees, and the Bishops and Prelats to the knaves of Clubbes, and other likeribaldry, and seditious raylinge” (5).

(With modern spelling the foregoing would read: “Anno Domini, 1529: he made a sermon on playing at Cards, and taught them how to play at Triumph, how to deal the Cards and what every sort thereof did signify, & that the Heart was the Triumph, adding moreover (saith Fox) such praises of that Cards (the Heart when it was Triumph) that though it were never so small, yet would it take up the best Cotecard besides in the bunch, yea though it were the Kinge of the Clubs himself, &c. Which handling of this matter was so apt for the time, and so pleasantly applied by him, that it not only declared a singular towardness of witt, but also wrought in the hearers much fruit, to the overthrow of Popish superstition, and setting up of perfect religion.

“Thus writeth Fox of the beginning of Latymer’s preaching in Cambridge, and of his playing at cards in the pulpit; a fit exordium for such a gospel, as after he was to preach, which commonly was everywhere begun with plays, comedies, puppets, jesting, assailing, railing of sedition, or other like practices (which Fox calleth setting up of perfect Religion) and not as Christ’s gospel began, with Agite poenitentiam, do penance, etc. And you must know that this Carding sermon of Latymer in Cambridge was one of the most spiteful and seditions that ever was heard before in England. For that under pretense of commending the Heart which was Triumph in the Cards, and represented (forsooth) his new Religion, he inveighed most bitterly against most points of Catholic Religion, as though they came not from the Heart: and consequently also compared the teachers thereof to Scribes and Pharisees, and the Bishops and Prelates to the knaves of Clubs, and other like ribaldry and seditious railings”).

The preaching of Latimer as described by Persons is not so absurd as it might seem at first sight. In fact, if we interpret the metaphor, it takes on a highly edifying meaning: the Ace of Hearts, and in general, all the cards of the same suit, are triumphant over the other suits of the cards, because in every situation the human spirit has to rely on the heart, on love, and therefore on goodness [hence the meaning of "having heart"]. Although the Ace of Hearts was lowly, it had more power than any other cards, including the King of Clubs. Here it must be said that the English word Clubs, in addition to being correlated with the French suit of Trefles, Flowers, can also mean batons, clubs, sticks, and it is in this sense that we must interpret the King of Clubs, which becomes the King of Clubs as Batons, coming to mean that the heart conquers all, even those who hold the power and who can hit or beat. It is indeed in this sense that we must interpret the phrase "compared .... Bishops and Prelates to the Knights of Clubbes" since it was the bishops, or religious authorities in general, who beat, with words, or worse with ferocious torture, those whom they considered as great sinners.

Certainly Persons did not make this argument. But it would be of little use, as there were many other of Latimer’s beliefs which contrasted with the sacred teachings of the Catholic Church. After his reconversion, at first to Catholicism ["driven by the cruel handlings of the Bishops" Persons quotes Foxe, however putting in doubt the veracity of that fact (6)], and t back to Protestantism, he imprisoned in the Tower by King Henry VIII to be, after the latter's death, released by King Edward VI. But then Edward died, and the Catholic Mary came to the throne. On October 19, 1555, Persons says (7), Latimer was burned at the stake. For Foxe, and the Church of England thereafter, he was a martyr for the true faith. For Persons he got what he deserved.

Notes

1 - John Foxe, Acts and Monuments..., London, John Day, 1563. Online at http://www.johnfoxe.org/

2 - Rober Persons, Third Part of a Treatise..., 1604, is online at at https://archive.org/details/thirdpartoftreat00pars. Parts One and Two, published together in 1603, had the title A treatise of three conversions of England from Paganisme to Christian Religion, the First under the Apostles, in the first age after Christ: the Second under Pope Eleutherius and K. Lucius, in the second age. The Third, under Pope Gregory the Great, and K. Ethelbert in the sixth age; with diuerse other matters thereunto apperteyning. Divided into Three Parts, as appeareth in the next page. The former two whereof are handled in this booke, and dedicated to the Catholikes of England. With a new addition to the said Catholikes, upon the news of the late Q. death, and succession of his maiestie of Scotland, to the crowne of England. To see it online click here.

3 - John Foxe, op. cit., pp. 1366-1378. Online starting at

http://www.johnfoxe.org/index.php?realm=text&gototype=modern&edition=1563&pageid=1366

4 - See: Robert Persons, 1604, op. cit., pp. 213-214.

5 - Robert Persons, 1604, op. cit, pp. 215-216. Here are Foxe’s own words in the 1563 original edition (pp. 1366-1367): "For on the sōday before Christēmas day commyng to the church, & causing þe Bel to be tolled to a sermō, entreth into the Pulpit. Vpon the texte of the gospel red that day in the churche Tu quis es? &c. in delyueryng hys cardes as is abouesayd, he made the hearte to bee tryumphe, exhortyng and inuityng al men therby to serue the Lorde with inwarde heart and true affection, and not with outwarde ceremonies: The difference betwixt trūe and false religion. addynge more ouer to the prayse of that triumphe, that though it wer neuer so smal, yet it wold make vp the beste cote carde beside in the bunche, yea thoughe it were the Kyng of Clubbes. &c. meanyng thereby, howe the Lorde would be worshipped and serued, in simplicitie of the hearte and veritie, wherein consisteth true Christian religion, and not in the outwarde dedes of the letter onely, or in the glisteryng shew of mans traditions, of pardons, pilgrimages, ceremonies, vowes, deuotions, voluntarye woorkes, and woorkes of erogation, foundations, oblations, the Popes supremacy. &c. so that al these either be nedelesse, where thother is presente, or els be of smal estimation in cōparison there of".

Or, in modern English: “For on the Sunday before Christmas day coming to the church & causing the Bell to be tolled to a sermon, entreth into the Pulpit. Upon the text of the gospel read that day in the Churche Tu quis es? &c in delivering his cards as is above said, he made the heart to be triumph, exhorting and intuiting all men thereby to serve the Lord with inward heart and true affection, and not with outward ceremonies. The difference betwixt true and false religion, adding moreover to the praise of that triumph, that though it were never so small, yet it would make up the best cote [court?] card beside in the bunch, yea though it were the King of Clubs &c, meaning thereby, how the Lord would be worshiped and served, in simplicity of the heart, and verity, wherein consisteth true Christian religion, and not in the outward deeds of the letter only, or in the glistering show of man’s traditions, of pardons, pilgrimages, ceremonies, vows, devotions, voluntary works, and works of erogation, fountains, oblations, the Pope’s supremacy, &c so that all these either be needless, where the other is present, or else be of small estimation in comparison thereof”].

6 - Robert Persons, op. cit., 1604 edition, p. 218.

7 - Ibid., p. 231.

ADDENDUM

by Michael S. Howard

HUGH LATIMER’S “SERMONS ON THE CARD”, 1529

Andrea in his essay calls our attention to a sermon that not only does not criticize the playing of card games, but in fact draws upon a game called "triumphs" to make a point about the teachings of the Gospels. Since it is 1529 and the preacher speaks of "hearts" being "trump", this game is not tarot but rather the game that assigns to one of the regular suits the role of trumps, so that any card of that suit beats any card of the other suits.

After reading Andrea's essay, I was interested in seeing Latimer's sermon itself, as opposed to the partisan summaries, including Foxe's. Since in 1529 King Henry VIII was still trying to get an annulment of his marriage from the Pope, I wondered whether the sermon actually was as described. Would a bishop of the Catholic Church in England at that time really dare to criticize the Papacy from the pulpit, even by means of subtle allusions? That is what my present essay is about: Latimer's actual sermon in relation to both Foxe and Persons.

The earliest edition of Latimer's sermons available to me (at my local library) is one called Fruteful Sermons, printed in 1635. It contains a dedication dated 1571. A list of Latimer's works in a 1906 modern edition of his sermons (Sermons by Hugh Latimer, Sometime Bishop of Worcerster, p. xvii) =has it that this collection was first published in 1572 and reprinted many times thereafter. No sermon of such a nature appears there. The first edition of Latimer's sermons was in 1562 and had the title Twenty-seven sermons of Hugh Latimer. I would expect it also to be lacking such a sermon.

From a remark of Foxe's, in fact, I would think that he was aware that the 1562 collection omitted what is of interest to us and saw this as something to be corrected. He says, (Foxe, 1563 edition p. 1367, at http://www.johnfoxe.org/index.php?realm=text&gototype=modern&edition=1563&pageid=1367&anchor=clubbes#kw):

« The copye and effect of these his sermons, although they were neither fully extracted, neither dyd they all come to oure handes, yet so many as came to our handes, I thoughte here to set abrode, for that I woulde wishe nothing of that man, whiche may be gotten to bee suppressed »

This is followed by a very lengthy document that appears to be what we are looking for, two sermons in fact. These same two sermons also appear as the first two sermons in the 1906 modern edition of his works, and with the same stipulation as Foxe gives them (p. 1367): "The Tenor and Effect of Certain Sermons made by Master Latimer in Cambridge, about the year of our Lord 1529"

(http://www.anglicanhistory.org/reformation/latimer/sermons/card1.html)

What follows, in 1906, except for modernizing the spelling, is almost word for word a copy of the texts that appear in Foxe's book. The two sermons are entitled "First Sermon on the Cards" and "Second Sermon on the Cards". Foxe had the same title for the second sermon but did not have one for the first sermon.

I conclude that the closest we are going to get to Latimer's original is what Foxe has given, pp. 1367-1373, which Latimer's 1906 editor considered reliable enough to include in a collection of his sermons.

The first sermon is indeed on the subject of Tu quis es?, Who art thou? It begins with an elaborate metaphor (p. 1368 in Foxe) involving the port of Calais, which although in France at that time was still in English hands. Then he answers his question, saying "I am a Christian man or woman". But what does that entail? He says what is required is "keeping to his [Christ's] rule", which "consisteth in many things, as in the commandments, and the works of mercy, and so forth." Then, Foxe p. 1369, comes his metaphor of the game of triumphs (I leave in the 1906 editor's explanation of the game).

« And for because I cannot declare Christ's rule unto you at one time, as it ought to be done, I will apply myself according to your custom at this time of Christmas: I will, as I said, declare unto you Christ's rule, but that shall be in Christ's cards. And whereas you are wont to celebrate Christmas in playing at cards, I intend, by God's grace, to deal unto you Christ's cards, wherein you shall perceive Christ's rule. The game that we will play at shall be called the triumph, [This game was something like the modern game of Whist. The cards, however, were not all dealt out; and the dealer had an advantage in being allowed to reject such cards from his hand as he thought proper, and take others in their stead from the undealt stock. An account of the game is given by Singer, "Researches into the History of Playing Cards, &c." pp. 269, 270.] which if it be well played at, he that dealeth shall win; the players shall likewise win; and the standers and lookers upon shall do the same; insomuch that there is no man that is willing to play at this triumph with these cards, but they shall be all winners, and no losers »

The cards, apparently, are metaphorically the elements of Christ's rule. Christ would thus seem to be the "dealer" of these cards. In this sermon Latimer is going to look at one "card", namely the commandment "Thou shalt not kill?" In what does that "card" consist? Here is the modernized text:

« Let therefore every Christian man and woman play at these cards, that they may have and obtain the triumph: you must mark also that the triumph must apply to fetch home unto him all the other cards, whatsoever suit they be of. Now then, take ye this first card, which must appear and be showed unto you as followeth: You have heard what was spoken to the men of the old Law, Thou shalt not kill; whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of judgment: but I say unto you of the new Law, saith Christ, that whosoever is angry with his neighbour, shall be in danger of judgment; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, Racha, that is to say, brainless, or any other like word of rebuking. hall be in danger of Council; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, fool, shall be in danger of hell-fire. This card was made and spoken by Christ, as appeareth in the fifth chapter of Saint Matthew »

Latimer is commenting on Matthew 5 verses 21 and 22, which read, in the 18th century Douay-Rheims Catholic translation, together with the Douay-Rheims' footnotes (http://www.drbo.org/x/d?b=drb&bk=47&ch=5&l=21#x):

« [21] You have heard that it was said to them of old: Thou shalt not kill. And whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment. [22] But I say to you, that whosoever is angry with his brother, shall be in danger of the judgment. And whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, shall be in danger of the council. And whosoever shall say, Thou Fool, shall be in danger of hell fire.

........................................................

[21] Shall be in danger of the judgment: That is, shall deserve to be punished by that lesser tribunal among the Jews, called the Judgment, which took cognizance of such crimes.

[22] Raca: A word expressing great indignation or contempt. Shall be in danger of the council ... That is, shall deserve to be punished by the highest court of judicature, called the Council, or Sanhedrim, consisting of seventy-two persons, where the highest causes were tried and judged, which was at Jerusalem.

[22] Thou fool: This was then looked upon as a heinous injury, when uttered with contempt, spite, or malice: and therefore is here so severely condemned. Shall be in danger of hell fire-- literally, according to the Greek, shall deserve to be cast into the Gehenna of fire. Which words our Saviour made use of to express the fire and punishments of hell »

Latimer sees four aspects of "Thou shalt not kill" in these verses of Matthew. He calls them "four parts of the card" (Foxe pp. 1369-1370)

« Now behold and see, this card is divided into four parts: the first part is one of the commandments that was given unto Moses in the old law, before the coming of Christ; which commandment we of the new law be bound to observe and keep, and it is one of our commandments. The other these parts spoken by Christ be nothing else but expositions unto the first part of this commandment: for in very effect all these four parts be but one commandment, that is to say, Thou shalt not kill. Yet nevertheless, the last three parts do show unto thee how many ways thou mayest kill thy neighbour contrary to this Commandment: yet, for all Christ's exposition in the three last parts of this card, the terms be not open enough to thee that dost read and hear them spoken...»

Since the three parts that Jesus has added may not be clear to his listeners, Latimer will explain them. The first part is feeling angry at another but not expressing that anger in word or deed (Foxe p. 1370):

«...a man which conceiveth against his neighbour or brother ire or wrath in his mind, by some manner o£ occasion given unto him, although he be angry in his mind against his said neighbour, he will peradventure express his ire by no manner of sign, either in word or deed: yet nevertheless he offendeth against God, and breaketh this commandment in killing his own soul; and is therefore in danger of judgment »

The second part is actually expressing the anger in words, with a more serious danger attached to it (Foxe p. 1370):

« Wherefore as he that so declareth his ire either by word or countenance, offendeth more against God, so he both killeth his own soul, and doth that in him is to kill his neighbour's soul in moving him unto ire, wherein he is faulty himself; and so this man is in danger of council »

Finally, to call someone "fool" is the third way of disobeying Christ's commandment, which merits "hell fire" (Foxe p. 1371):

«...for to call a man fool, that word representeth more envy in a man, than brainless doth. Wherefore he doth most offend, because he doth most earnestly with such words express his ire, and so he is in danger of hell fire »

I can see that expressing contempt is more insulting than merely expressing anger, but I am not myself sure what the difference is between "fool" and "brainless". Perhaps "fool" had a different connotation than it does today. According to Persons, a “gray friar” had in that year of 1529 “raged against Maister Latymer callinge him a [i]madd and brainless man[/i]” (p. 217). Perhaps Latimer’s sermon is in a way a reply to that charge. If so, perhaps “fool” had the meaning of “madman” as opposed to “brainless”. Persons, in calling Latimer a “buffoon” and his sermon "clownish", would seem to be following in the footsteps of the “gray friar” (presumably the same as the “Augustinian” Foxe mentions, who “took occasion...to inveygh against him”, p. 1366).

These three parts of the card, according to Matthew 5:21-22, have progressively worse punishments in hell. For the third, he says (Foxe p. 1371):

« Hell fire is a more pain in hell, than council or judgment, and it is ordained for him that calleth his neighbour "fool," by reason that in calling his neighbour "fool," he declareth more his malice, in that it is an earnest word of ire: wherefore hell-fire is appointed for it; that is, the most pain of the three punishments »

A rather live issue in 1529 was the threat of the Turks against Christian lands. But unlike other preachers, Latimer does not invoke the Turks so as to wage war against them. Instead, Latimer invokes the metaphor of hearts as trumps, by which to subdue the “Turks”, now a metaphor for our evil-disposed inclinations (p. 1371):

« These evil-disposed affections and sensualities in us are always contrary to the rule of our salvation. What shall we do now or imagine, to thrust down these Turks and to subdue them? It is a great ignominy and shame for a christian man to be bond and subject unto a Turk: nay, it shall not be so; we will first cast a trump in their way, and play with them at cards, who shall have the better. Let us play therefore on this fashion with this card. Whensoever it shall happen the foul passions and Turks to rise in our stomachs against our brother or neighbour, either for unkind words, injuries, or wrongs, which they have done unto us, contrary unto our mind; straightways let us call unto our remembrance, and speak this question unto ourselves, "Who art thou?" The answer is, "I am a christian man." Then further we must say to ourselves, "What requireth Christ of a christian man?" Now turn up your trump, your heart (hearts is trump, as I said before), and cast your trump, your heart, on this card; and upon this card you shall learn what Christ requireth of a christian man, not to be angry, nor moved to ire against his neighbour, in mind, countenance, nor other ways, by word or deed. Then take up this card with your heart, and lay them together: that done, you have won the game of the Turk, whereby you have defaced and overcome him by true and lawful play »

I am not sure what rule Latimer is imagining for this game. Apparently it involves two cards: the one card "Do not kill" and another card, the heart. A person is to "lay them together". I do not know any such game, but this interpretation is confirmed by the "second sermon on the card", where he adds a third card, saying (Foxe, p. 1375):

« By and by cast down your trump, your heart, and look first of one card, then of another. The first card telleth thee, thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not be angry, thou shalt not be out of patience. This done, thou shalt look if there be any more cards to take up; and if thou look well, thou shalt see another card of the same suit, wherein thou shalt know that thou art bound to reconcile thy neighbour. Then cast thy trump upon them both, and gather them all three together, and do according to the virtue of thy cards; and surely thou shalt not lose »

Returning to the first sermon, I see another description of the game that I do not recognize, that of "breaking" a card and "playing the blind trump" (Foxe p. 1372):

« And so you may perceive that there be many a one that breaketh this card, Thou shalt not kill," and playeth therewith oftentime at the blind trump, whereby they be no winners, but great losers. But who be those nowadays that can clear themselves of these manifest murders used to their children and servants? I think not the contrary, but that many have these two ways slain their own children unto their damnation; unless the great mercy of God were ready to help them when they repent therefore »

By "their children and servants" Latimer means one's own angry thoughts and actions. “Breaking” might simply mean the destruction of a card, taking it out of the game. I do not know what it is to play a "blind trump". Perhaps someone who knows the game can tell us.

He ends the first sermon with the example of Mary Magdalene, whom Christ allowed to wash his feet, although the "Pharisees" treated her with disdain because of her low status and her sins. Those who disdain the sinner who forsakes his or her sin is like the Pharisee with Magdalene (p. 1372):

« And think you not, but that there be amongst us a great number of these proud Pharisees, which think themselves worthy to bid Christ to dinner; which will perk, and presume to sit by Christ in the church, and have a disdain of this poor woman Magdalene, their poor neighbour, with a high, disdainous, and solemn countenance? »

Again, what matters is the commandment “Do not kill” as Christ interprets it, not to be disdainful of others. Latimer concludes (Foxe p. 1372f:

« If we be the true Magdalenes, we should be as willing to forsake our sin and rise from sin, as we were willing to commit sin and to continue in it; and we then should know ourselves best, and make more perfect answer than ever we did unto this question, "Who art thou?" to the which we might answer, that we be true christian men and women: and then, I say, you should understand, and know how you ought to play at this card, "Thou shalt not kill," without any interruption of your deadly enemies the Turks; and so triumph at the last, by winning everlasting life in glory »

I do not understand what "without interruption” means here. Otherwise the meaning is clear enough.

In the second sermon, as already mentioned, he talks about a second "card", that is, the rule or commandment to make amends to those one has sinned against. I think he is referring to the verses immediately following the passage he talked about in his first sermon (about Christ's three additional ways of violating the commandment "Do not kill", Matt. 5:21-22). Matthew 5 goes on to say, in verses 23-25, in the Douhy-Rheims translation (http://www.drbo.org/x/d?b=drb&bk=47&ch=5&l=21#x):

« [23] If therefore thou offer thy gift at the altar, and there thou remember that thy brother hath any thing against thee; [24] Leave there thy offering before the altar, and go first to be reconciled to thy brother: and then coming thou shalt offer thy gift. [25] Be at agreement with thy adversary betimes, whilst thou art in the way with him: lest perhaps the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison »

Latimer puts this “rule”, to reconcile with one's brother, in the context of various acts of penance encouraged by the church and finds them of no consequence unless the rule of making amends is done as well, to the extent one is able; only then can one hope for reconciliation with God (p. 1375):

« But yet Christ will not accept our oblation (although we be in patience, and have reconciled our neighbour), if that our oblation be made of another man's substance; but it must be our own. See therefore that thou hast gotten thy goods according to the laws of God and of thy prince. For if thou gettest thy goods by polling and extortion, or by any other unlawful ways, then, if thou offer a thousand pound of it, it will stand thee in no good effect; for it is not thine. In this point a great number of executors do offend; for when they be made rich by other men's goods, then they will take upon them to build churches, to give ornaments to God and his altar, to gild saints, and to do many good works therewith; but it shall be all in their own name, and for their own glory. Wherefore, saith Christ, they have in this world their reward; and so their oblations be not their own, nor be they acceptable before God »

Building churches, giving ornaments, gilding saints, etc., are what Latimer calls "voluntary works", as opposed to "necessary works", i.e. the following of Christ's law, and "acts of mercy", both of which take precedence (p. 1375):

«...setting up candles, gilding and painting, building of churches, giving of ornaments, going on pilgrimages, making of high-ways, and such other, be called voluntary works; which works be of themselves marvelous good, and convenient to be done.” But unless the "necessary works" are done, these are of no consequence in the eyes of God »

It seems to me that Latimer is attacking the Catholic Church here only in so far as it might have implied or taught that "voluntary works" can be done in the place of Christ's commandments, which he calls "necessary works". I do not know what Catholic doctrine was at that time; it is not, to one as unschooled as I, an obviously anti-Catholic sermon,

Persons opposes the Gospel’s Agite poenitentiam, “Do Penance” to Latimer’s downgrading of extraordinary monetary support for the Church, pilgrimages, etc. as an act of penance. But it seems to me more a matter of what kinds of penance are most important, and what kinds of damage need to be repaired by penance. Latimer is saying that to repair the damage to one’s relationship to God one must first repair the damage to one’s relationship to one’s fellow humans. Latimer sees in the Gospel a social message as part of the spiritual one. It is not a question of works vs. faith. It is only a question of which works to perform so as to fulfill Christ’s commandments.

Latimer in these sermons seems to me not nearly as anti-Catholic as Persons makes him out to be; I see little difference between him and Erasmus, who was greatly influential in the England of Latimer’s earlier days. Although after the Council of Trent, all of Erasmus’s books were put on the Index, his works were not banned in his lifetime, and he was not excommunicated or subjected to disciplinary measures.

Persons in his estimation of Latimer may have been misled by Foxe. Let us look at Foxe's introduction to the sermons, which he gives just before the text of their "tenor and effect", so as to compare it with those texts. Here is what he says, in modernized spelling (Foxe p. 1366f):

“...master Latimer in the said sermons, (alluding to the common usage of the season) gave the people certain cards out of the 5th, 6th, [and] 7th chapters of St. Matthew, whereupon they might, not only then, but always else, occupy their time. For the chief (as their triumphing card) he limited the heart as the principal thing that they should serve God withal: whereby he quite overthrew all hypocritical and external ceremonies, not sending in [including?] the necessary beautifying of god's holy word & sacraments. For the better attaining hereof, he wished the scriptures to be in English, that the common people might thereby learn their duties, as well to God, as to their neighbors.

« The handling of this matter was so apt for the time, and so pleasantly applied of Latimer,that not only it declared a singular towardness of wit in him that preached, but also wrought in the hearers much fruit, to the overthrow of popish superstition, & setting up of perfect religion. For on the Sunday before Christmas day coming to the church and causing the Bell to be tolled to a sermon, [he] entereth into the Pulpit. Upon the text of the gospel read that day in the Churche Tu quis es? etc. in delivering his cards as is above said, he made the heart to be triumph, exhorting and intuiting all men thereby to serve the Lord with inward heart and true affection, and not with outward ceremonies. The difference betwixt true and false religion, adding moreover to the praise of that triumph, that though it were never so small, yet it would make up the best court card beside in the bunch, yea though it were the King of Clubs etc., meaning thereby, how the Lord would be worshiped and served, in simplicity of the heart, and verity, wherein consisteth true Christian religion, and not in the outward deeds of the letter only, or in the glistering show of man’s traditions, of pardons, pilgrimages, ceremonies, vows, devotions, voluntary works, and works of erogation, fountains, oblations, the Pope’s supremacy, etc., so that all these either be needless, where the other is present, or else be of small estimation in comparison thereof »

If the heart triumphs, Foxe says, then "man’s traditions, of pardons, pilgrimages, ceremonies, vows, devotions, voluntary works, and works of erogation, fountains, oblations, the Pope’s supremacy, &c" are "needless or of small estimation" when the "simplicity of the heart" is present. But this is clearly a misinterpretation of Latimer's words, and metaphor, as he gives them later. Latimer did not say that [i]all[/i] one needs was heart, There are also the "necessary actions", namely, Christ's rules, which for Latimer are the "commandments and acts of mercy", done in a heartfelt way. These come first. And then, if one has resources and time, pilgrimages, ornaments, etc. are also good and "ought to be done". Foxe has not seen that in Latimer's card game—as opposed, I assume, to the usual game of triumphs--one must play not just the trumps, in this case hearts, but with them the winning cards that Christ has dealt the players; those cards are his commandments.

It would seem that the winning cards, i.e. the cards with points, which determine the winner, are the commandment cards and not the trumps. The trumps, the hearts, are merely the means by which one accomplishes the commandments. In the game, the trumps are not in themselves the point-getters, but rather the means for obtaining the point-getters, which in the case of tarot (and presumably triumphs) were mainly the court cards. In Latimer’s game, however, the point-getters are the commandments—which are not captured from others but played oneself.

The reference to the King of Clubs, too, is Foxe's, not Latimer's. Persons also mentioned a “Knight of Clubbes” but there is no mention of such a card at all, in either Latimer or Foxe. (This term in itself is of interest: did English decks have “Knights”, as opposed to “Jacks” then? Perhaps so.) Persons' insinuation seems to be that if the Knight of Clubs are bishops, etc., then the King of Clubs would be the Pope. I don't know if Foxe meant the Pope in that metaphor or not. It might be a reference to King Henry VIII or monarchs in general, who held the power of life and death over their subjects; it was when Latimer disagreed with Henry over his “Six Articles” of the faith that Henry removed him from his bishopric and confined him to the Tower.

For me, both Foxe and Persons do Latimer an injustice in their characterizations of Latimer’s sermons. They serve to show, as we know, that second-hand paraphrases represented as repeating what another said, in the hands of a partisan reporter, are likely to be distorted. But at least Foxe had the decency to include something besides his own partisan summary, something approximating direct quotation that he probably didn't write himself since it conflicts with that summary). That long text was as available to Persons as it is to us.

The sermons also show the popularity of the game of triumphs at that time in Cambridge. Perhaps indeed some people thought of Latimer's metaphor when playing the game during the Christmas holidays. Unfortunately Latimer’s metaphor, at least as we have it, probably did not correspond exactly to the game that people played.

Finally, I am struck by the similarity of Latimer’s views to those of some humanists in 15th century Italy. Starting with Lorenzo Valla, they questioned the Church’s interpretation of “Agite poenitentiam” and other instances of the Vulgate’s Latin.. Some, like Traversari (I get this from Krautheimer, Ghiberti, vol. 1, p. 177; see my post at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1049&p=15800&hilit=Bible#p15800), called for a faithful translation of the Bible into the vernacular (which Foxe says Latimer did). They, too, stressed the need to do charitable works and opposed with the wordliness of the Papacy of their time. Like him they enjoyed extended allegories. Like him, they knew a game called “triumphs”. It seems to me that Latimer’s sermons might therefore give us insight into how those humanists might have seen the first game with rules similar to that of Latimer’s “triumphs”, i.e. the tarot.