Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, June 2013

To find at last a writing by Bruno in which he quotes the Tarot is something extraordinary, if you consider that Bruno was one of the most important men of the Renaissance to adopt the Art of Memory, also as a philosophical key. The tarot, with its rich images of symbols and allegories, was nothing less than a large mnemonic fresco built for the people of the time, which contained the wonders of the visible and invisible world and gave instructions to its players on the physical, moral and mystical levels (on this read our essay The History of the Tarot). Peter of Ravenna, one of the most famous theologians of the '"ars memorativa" of the Renaissance, stated that images, which needed absolutely not to be sinful, had to excite the imagination in a chaste and not sinful way. Such are the figures of the tarot, which at a distance of hundreds of years after their creation are still able to evoke a multitude of arcane meanings.

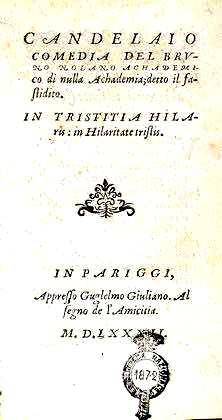

Giordano Bruno speaks of tarot in a comedy, the only one he wrote, accustomed as he was to write philosophical treatises and dialogues. This is the Candelaio, which he composed during his stay in Paris in the summer of 1582. [The term Candelaio means not only “Candlemaker”, but also “Candlebearer” and “Candlemas”, and - its main use in the play - is a slang term for a certain sexual proclivity]. Mystery (the work is dedicated to a mysterious Morgana), magic (the rituals of a necromancer to induce love), satire (against religion, in the sense of "religio"), critique (especially against the imposture of miracles), parody (emphasizing the total indifference of the gods towards human actions), superstitious beliefs (the practice of reciting prayers for all sorts of adversity even for those with which a religious person would have had nothing to do), the condition of human unconsciousness (exempting only individuals excellent in their ability to restore order to the chaos of the world) are the main ingredients of this comedy, where the tones of the language often border on obscenity, a vulgarity which consistently reflects the characters, who are none but vulgar and immoral people. The tones could not, therefore, be other than those of a raw and harsh realism, tones that brought the eighteenth century to condemn the play as "wicked and vile" and to be considered by Carducci as "grossly indecent and boring." For our part, we found it, on the contrary, delicious. Let us read for example the Dedication to the enigmatic Morgana:

To the Signora Morgana B., his always honored lady

"And I, to whom shall I dedicate my Candelaio ? To whom, O great destiny, does it please you that I devote my beautiful paranymph, my fine chorus leader? To whom shall I address that which from Sirius’s heavenly influence, in these most sweltering days, and most searing hours, called the dog days, the fixed stars have made rain in my brain, the blurry fireflies [lucciole, also prostitutes] of the firmament above have sifted [also, riddled] on me, the decans of the twelve signs shot into my head, and the seven wandering lights blown in my inner ear? To whom hath it turned, - I say, - at whom does it take aim? At His Holiness? no. At His Imperial Majesty? no. At His Serenity? no. At Her Highness, the most illustrious and reverend Ladyship? no, no. By my faith, it is no prince or cardinal, king, emperor or pope to whom my hand raises this candle, in this solemn offertory. To you who touch it, to you it is given, and you shall secure [attaccarrete, also, per Florio, “tumble”, as in “tumbling a wench”] it in your Cabinet or stick [ficcarette, related to fig] it into your candle holder, my most superlatively learned, wise, beautiful and generous s[ignore] Morgana: You, cultivator [cultivatrice] of the field of my soul, who, after having broken up its clods of their hardness and refined its style - in order that the dust cloud raised by the wind of levity should not offend the eyes of this and that person - with divine water, which comes from the fount of your spirit, to water my intellect. Well, at the time when it was possible to touch hands, I first addressed to you: Gay thoughts; and after:

The trunk of living water.

Now, between you, who enjoy the bosom of Abraham, and me, who desperately burns and blazes without hope of your succor that alone is cooling to my tongue, is put a great chaos, too envious of my good; but to show you, with some proper pledges and the present material, that this selfsame chaos cannot obstruct my love by its rotten spite, here then comes the candle offered from my hand to yours, this Candelaio, which is parted from me, to perhaps, in this country where I find myself, bring light to some certain Shadows of ideas [the name of Bruno’s first book], which in truth scares the beasts, and like Dantian devils, makes the donkeys remain far behind; and may, in the homeland where you are, may make it possible for many to contemplate my spirit, and show that it has not at all quit.

Say hello from me to that other Candelaio of flesh and bones, of whom it is said that "Regnum Dei is not possidebunt" [“They” - among them sodomites, the sexual meaning of “Candelaio” - “shall not inherit the Kingdom of God”, I Cor. 6:9-10] and tell him not to enjoy so much that my memory is said to have been scrambled by the force of pigs’ feet and the kicking of asses, because at this time the donkeys have cropped ears, and the pigs some December will be paying me. And may he not enjoy so much the saying: "Abiit in regionem longinquam" [“He lives in a distant country,” close to Luke 15:13], because if the heavens ever grant that I can effectively say: "Surgam et ibo" [I will arise and go, Luke 15:18], this fatted calf undoubtedly will be part of our feast. Between now and then, may he live and govern himself, and hope to be fatter than he is, because, on the other hand, I hope to recover lard where I lost the grass, if not under one cloak, under another, if not in one, then in another life. Remember, Lady, what I believe, which there is no need to teach you: - Time takes everything and gives everything, everything is changed, nothing is destroyed, there is one alone that cannot change, one alone is eternal, and can endure eternally one, similar and the same. - With this philosophy my spirit grows larger and magnifies my intellect. But, whatever the point of this evening of waiting, change is real; I. that am in the night, wait for the day, and those who are in the day, wait for the night, all that is, whether here or there, near or far, now or then, sooner or later. Enjoy, then, and, if possible, be healthy, and love who loves you".

The story takes place in Naples in the sixteenth century, where Messer Bonifacio, the candelaio, yearns beyond measure for the Lady Victoria, although he is already married to Carubina. Bonifacio, together with Manfurio and Bartolomeo, the first a pedantic gull and the second a novice alchemist, becomes the subject of fraudulent intentions by some crooks, in cahoots with the same Victoria, who aim to take advantage of Bonifacio’s love to pry loose a bit of his money. The latter, consumed by a passion for the woman, relies on the magic of Scaramuré hoping for some kind of well-made spell to make the evil Victoria fall in love with him. The spell seems to have succeeded, and a meeting is fixed between the two, but instead of Victoria, Carubina intervenes, outraged by the behavior of Bonifacio, and decides to let herself be seduced by her suitor Gioan Bernardo, convinced that putting horns on husbands like that was not after all a grave thing, but necessary. Manfurio and Bartolomeo will be mocked, robbed and beaten also.

The characters listed are not the only ones in the play, who are much more numerous:

Bonifacio, in love with Vittoria

Bartolomeo, alchemist

Manfurio, pedant

Vittoria, lady

Lucia, procuress

Carubina, wife of Bonifacio

Gioan Bernardo, painter

Scaramuré, necromancer

Ottaviano, facetious spirit

Pollula, student of Manfurio

Cencio, crook

Marta, wife of Cencius

Consalvo, apothecary

Sanguino, rogue

Barra, rogue

Marca, rogue

Corcovizzo, rogue

Ascanio, servant of Bonifacio

Mochione, servant of Bartolomeo

The Candelaio is presented as a "Comedy of Bruno the Nolan - Academic of no Academy; called Il Fastidito [the troubled, annoyed]" with the addition of the sentence “In tristizia hilaris, in hilaritate tristis” ["In sorrow laughter in hilarity sorrow]".

The epigraph of the play, In tristitia hilaris in hilaritate tristis, makes the reader thoughtful, revealing the state of mind of the young monk, who even then portrayed himself as one of those who sketched everything (1): "The author, if you become acquainted with him, says he is a lost soul: he seems to always be in the contemplation of the torments of hell, like his fingers were in a press: laughing only to be like others: for the rest, you will see a fastidito, restless and bizarre, he is not content with anything, like an old man of eighty, doleful as a dog that has received a thousand beatings and been fed onions." There is certainly sadness in the hilarity of Bruno when with Mephistophelean irony he puts philosophers into the category of such people as “By the blood, I will not say whose, he and all these other philosophers, poets and pedants, their greatest enemy is wealth and goods, which, for fear of being torn to pieces by them in earnest, quartered and dissipated, while being anatomized by their brains, flee them as from a hundred thousand devils, and go to find again those that keep them healthy and preserved. So much so that having been served by similar rogues, I have had lots of hunger, lots of hunger, so that if I needed to vomit, I could not vomit anything but spirit, if I had the strength to shit, I could not shit anything but soul, like someone hanged. In conclusion, I want to go to become a monk, and whoever wants to do the prologue should do it". Likewise, it is sad in its hilarity when he observes that there is little in the world of beauty and nothing good, and most of all those who believe, most mistaken, in the reigning universal love of money (2).

The author clarifies, in the Argument and Order of the Comedy, the main topics dealt with and then follows with a host of other situations:

"There are three main subjects woven together in the present comedy: the love of Bonifa[cio], the alchemy of Bartolomeo, and the pedantry of Manfurio. However, for a distinct understanding of these subjects, a reasoned explanation of their order and evidence of the textual artifice, we report first the insipid lover, second the sordid miser, third the oafish pedant: of which the insipid is not without oafishness and sordidness, the sordid is likewise insipid and oafish, the oafish is no less sordid and insipid than oafish .... You will see also in great confusion the methods of rascals, the stratagems of thieves, the undertakings of villains; moreover, sweet dislikes, bitter pleasures, foolish resolves, failed faith, crippled hopes and meager charity, great and severe judgments in other people's business, with little appreciation for one’s own; virile women, effeminate men: many voices from the mouth but not from the heart, how he who believes the most is the most deceived, and the universal love of money. Thus proceed quartan fevers, spiritual cankers, weightless thought, rubbish overflowing, stumbled upon conceits, masterful blunders, and falls that break one’s neck; otherwise, desire that moves one, knowledge that bears fruit, and diligence mother of success. In conclusion, it will not have all things for sure, but much activity, enough defects, little beauty, and nothing good. - I think I hear the characters; good-bye".

The passage where Bruno cites the Tarot expresses a typical moment in the life of Naples in a time when "the least of the Neapolitan people will present you in dialogue, with promptness and copiousness, witty sayings and an abundance of proverbs, judgments, invocations to the saints, and blasphemies, which are a quality particular to the character and customs there. We can cite, for example, all the scenes of the group of fake policemen, and those specifically of Marca and Barra, who tell each other the hoaxes conducted in the tavern of Cerriglio in Naples and that of Pumigliano". (3)

In reference to this we report the whole of Act III Scene Eight:

ACT III – Scene 8

Marca, rogue

Barra, rogue

Marca: Do you see Master Manfurio leaving?

Barra: Let him leave with the devil! Let’s stay here; continue the story.

Marca: Now then, last night, at the inn of Cerriglio, after we had eaten very well, having nothing better to do, we sent the innkeeper off after things like cloves, pumpkin seeds, quince jelly and other bagatelles, just to pass the time. When we knew of nothing more to ask, one of us feigned a fit. And to the host coming running with some vinegar, I said: “Aren’t you ashamed, you mean little man! Go get some rose water, some orange brandy, and bring some wine of Candia”. The innkeeper refused, and began to yell, saying “In the name of the devil, are you marquesses or dukes? Or are you people who renege on what you’ve spent? I’m not even sure you can pay the bill. Anyway, what you are asking for isn’t something in an inn.” “Blackguard, scoundrel, thief,” I say, “Do you think you are dealing with people like yourselves? You are a horned goat [a cuckold] and a fool.” “You lie by a hundred throats,” said he. So, all of us together, for our honor, got up from the table and each of us grabbed a skewer, a large one, ten palms long.

Barra: Good start, sir.

Marca: ... and some even had food on them, and the innkeeper runs to get a pike; and two of his servants with two rusty swords.. But we were six with six skewers longer than his pike, and we also grabbed some warming pans, to use as round shields ...

Barra: Wisely.

Marca: ... A few of us put certain pots of bronze on our heads as helmets ...

Barra: It was certainly some constellation [i.e. lucky stars] that gave you the inspiration to grab the skewers, pots and pans.

Marca: ... And thus well armed and covered, we defended ourselves by backing out down the stairs, toward the door, although we pretended to step forward ...

Barra: "Good fighting! One step forward and two back, one step forward and two back" as Cesare da Siena used to say.

Marca: ... The innkeeper, when he saw us much stronger, but acting more timidly, instead of glorying in his dominance, entered into some suspicion:

Barra: Anyone would have.

Marca: ... with that, he threw the pike on the floor, commanded his servants to draw back, because he did not wish any revenge on us ...

Barra: A soul good enough to canonize.

Marca: He turned to us and said: "Gentlemen, gentlemen, pardon me, I sincerely do not want to offend you! By your grace, pay me and go with God!

Barra: That would have been good with [the addition of] some penance for absolution.

Marca: "You want to kill us, you traitor" I said, and with that we put our feet out the door. Then the desperate innkeeper, realizing that we did not accept his kindness and devotion, resumed with the pike, calling more servants, sons and wife. It was good to hear! the innkeeper yelled: "Pay me, pay me"; others screeched: "Cutpurses, Cutpurses, ah, thieves, traitors!" With all that, no one was so crazy to run after us, because the darkness of the night favored us more than them. We, therefore, fearing the hostile wrath, that is of the landlord, fled to a room in the Carmelite quarter]; where, counting our money, we had [saved] enough for three days.

Barra: To play a joke on an innkeeper is to make a sacrifice to Our Lord; to rob an innkeeper is to perform an act of charity; a good beating has merit enough to release a soul from purgatory! - Tell me, did you know what happened afterwards at the inn?

Marca: Many gathered, some amused, others offended, others crying, others laughing, these advising those hoping, different kinds of faces, this language and that: seeing together comedy and tragedy, and some celebrating and some mourning. Of the sort, that if you wanted to see how the world is, you’d want to have been there.

Barra: Truly it was good. - But I don’t know much about rhetoric [i.e. clever speaking], all alone, without companionship, the day before yesterday, coming from Nola to Pumigliano, after I had eaten well, not having too much desire to pay, I said to the innkeeper: "Messer host, I would like to play a game". "What game," he said, "do you want us to play? I have tarot cards". I said, "In this cursed game I cannot win, because I have a terrible memory". ["A questo maldetto gioco non posso vencere, perché ho una pessima memoria"]. He said: "I have ordinary cards". I said, "They may have been marked so that you would know them. Do you have any new ones that have not been used?" He said not. "So we’ll think of another game." "Do you know boards [tavola, might be dominos]?" "Of this I know nothing". "I have chess, do you know it?" "This game would make me deny Christ". Then he went into a rage: "Then what devil of a game you want to play? Suggest something". I say: "One sending off a ball with a mallet". Said he: "What game with mallet? Do you see any of these things here? Do you see any space to play?" I said, "Darts?" "That’s a game for porters, yokels and pig-farmers". "Five dice". "What the devil is five dice? I’ve never heard of this game. If you want, we’ll play three dice.

I told him that with three dice I had no luck. "In the name of fifty thousand devils," he said, "If you want to play, propose a game that we can do, you and I". I said, "Let’s play spin the top". “Go on,” he said, "You’re giving me nonsense: this game is for children, are not you ashamed?" "Come on, then," I said, "Let’s play running [correre]" ."Now, this is not a real game," he said. And I replied: "By the blood of the Virgin, it is a game!" "If you want to do well," he said, "pay me, and you if do not want to go with God, go with the prior of the devils!" I said, "By the blood of the scrofula [a form of tuberculosis], you’ll play!" "And if I do not play?" he said. "And if you do play?" I said. "And if I never ever will play?" "And if you are going to play now?" "And if I don’t want to?" "And if you do want to?" In the end, I began to pay with my heels, that is, to run, and behold, that pig who had just said that he did not wish to play, and swore that he did not wish to play, and swore that he did not wish to play, he did play, and two of his workers also played: so well that, after a while running close to me, they reached me ... with their voices. Then, I swear, by the huge wound of St Rocco, I did not hear more, nor did they see me".

Marca: I see Sanguino and m[esser] Scaramuré coming".

At the beginning of the article we underlined the importance of this work in reference to the fact that Giordano Bruno was an extraordinary author of the study of the art of mnemonics. In this situation what is most interesting is the fact that Bruno, talking about tarot cards. put into the mouth of the rogue Barra the words "In this cursed game I cannot win because I have a terrible memory". A sentence with which the author qualifies himself by being alien to the nullity of the mediocre.

Bruno taught art of memory and was famous for his memory. So the phrase of Barra “In this cursed game I cannot win because I have a terrible memory”, means that Bruno, who has a wonderful memory, is far from the world of idiots without memory, men of little value, mediocre men.

Notes

1 - Antiprologue. [Translation based on that of Gino Moliterno, in Giordano Bruno, The Candlebearer, Dovehouse Editions, Ottawa, Canada, 2000, p. 67f. The present translator has compared Moliterno’s, which is a performing version, with the Italian text and made occasional substitutions to make the translation more closely follow the text. The same procedure has been followed for the other quotations from Bruno in this essay. The comments in brackets here are either from Moliterno or from information in John Florio’s 1611 Italian-English dictionary, http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/florio/].

2 - Proprologue. [Translation based on that of Moliterno p. 71f.]

3 - Domenico Berti, Vita di Giordano Bruno da Nola, [Life of Giordano Bruno of Nola], 1868, pp. 145-146.

Copyright by Andrea Vitali - © All rights reserved 2009